Machines of loving taste

Music and media streaming is an economically, ethically complex problem

Long overdue thanks: to Stephanie Dukich and Manasa Karthikeyan for organizing and running the reading group and lecture series Death to Spotify Forum: Decentralizing Music from Capitalist Economies (SFGATE: sold out in 24 hours); to Bathers Library for being the hottest underground club in Oakland every Tuesday night; to the guest speakers and discussion group members for sharing their personal and motivating reflections on how and why we listen to and talk about music; to Zareen Choudhury for sending me the class information and leading the charge socially to prioritize intentional media consumption; to Mercury Cafe and Mother Tongue for fueling and providing space for my writing; to my friends and loved ones for believing in me and being lights that guide my path in our brave new world.

Find me on X @valstechblog.

The title of this post is a reference to Machines of Loving Grace by Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei this month last year, itself a reference to Richard Brautigan’s 1967 poem. In it, he described “what a good world with powerful AI could look like”, highlighting the potential for transformative advances in physical and mental health technology, economic growth, inequality mitigation, climate and food supply, and governance systems.

I don’t know if this world is realistic, and even if it is, it will not be achieved without a huge amount of effort and struggle by many brave and dedicated people. Everyone (including AI companies!) will need to do their part both to prevent risks and to fully realize the benefits.

…It is a world worth fighting for. If all of this really does happen over 5 to 10 years—the defeat of most diseases, the growth in biological and cognitive freedom, the lifting of billions of people out of poverty to share in the new technologies, a renaissance of liberal democracy and human rights—I suspect everyone watching it will be surprised by the effect it has on them.

Basic human intuitions of fairness, cooperation, curiosity, and autonomy are hard to argue with, and are cumulative in a way that our more destructive impulses often aren’t… We have the opportunity to play some small role in making it real.

I’ll admit I attended the Death to Spotify Forum with an explicit intention to get out of the San Francisco tech bubble and to challenge myself to rethink and rework the ways I consume and interact with music and media. I wanted to emerge from Oakland five weeks later a boombox-sporting, vinyl-spinning, radio-supporting connoisseur of underground music. At minimum, I hoped to come away with a stronger sense of identity and morals as a musician and consumer.

Perhaps unsurprisingly in retrospect, I did the opposite. I’d hear our guest speakers talk about the brief magic of chancing upon music that made them feel a certain way, and I’d be reminded of my own surprise and delight at the ~0.1% of my YouTube recommendations that stuck with me: what made YouTube a sparse but high-quality recommendation system? Record label owners and radio station hosts discussed the complexities of reaching and engaging with their audience in a streaming-first economy, and I’d start thinking about ways to tip economic incentives at scale, how to make streaming alternatives more compelling for customers. We talked about the existential struggle indie bands face these days if they’re not on social media, and I thought to myself, “We can abstract that away for them.”

I thought about scalable systems design, which might sound far-fetched at first, but actually became a single unifying principle for me over the weeks. I realized that my friends and I might be able to intentionally rewire our brains for longer-term gratification, delete our social media, and move off streaming services. There is value to living a more unplugged life. But being totally offline isn’t accessible or realistic for much of the world. We are privileged to have so much stimulus in our lives that we can decide which ones to turn off. I was torn between voting with my actions by boycotting attention-based technology — turning back to offline, old-school methods — and becoming a majority consumer myself so I could identify the core incentives motivating our media consumption patterns. I wanted to piece apart what was systemically broken and work to fix it. How do we build a better future for ourselves without first understanding how we got here? How do we design for disparately-distributed populations of which we are miniscule segments?

To stream or not to stream: the artist’s conundrum

In the first week of reading group, we discussed Liz Pelly’s pieces on Spotify (Big Mood Machine and The Ghosts in the Machine) describing advertisement packages based on users’ moods and lifestyles inferred from music listening behavior and an internal “Perfect Fit Content” program that pushed playlist curation and the music itself in lower-cost directions for the company. We read about a wave of artists including King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard boycotting Spotify over demonetization of already low payouts to grassroots artists, a growing and unsolved AI-generated music problem, and Daniel Ek’s investments. We talked about how we discovered some of our favorite artists on Spotify in the past, how we now found ourselves passively letting the algorithm decide what we should listen to, how we were increasingly dissatisfied with our recommendations but also didn’t necessarily know what else would be better.

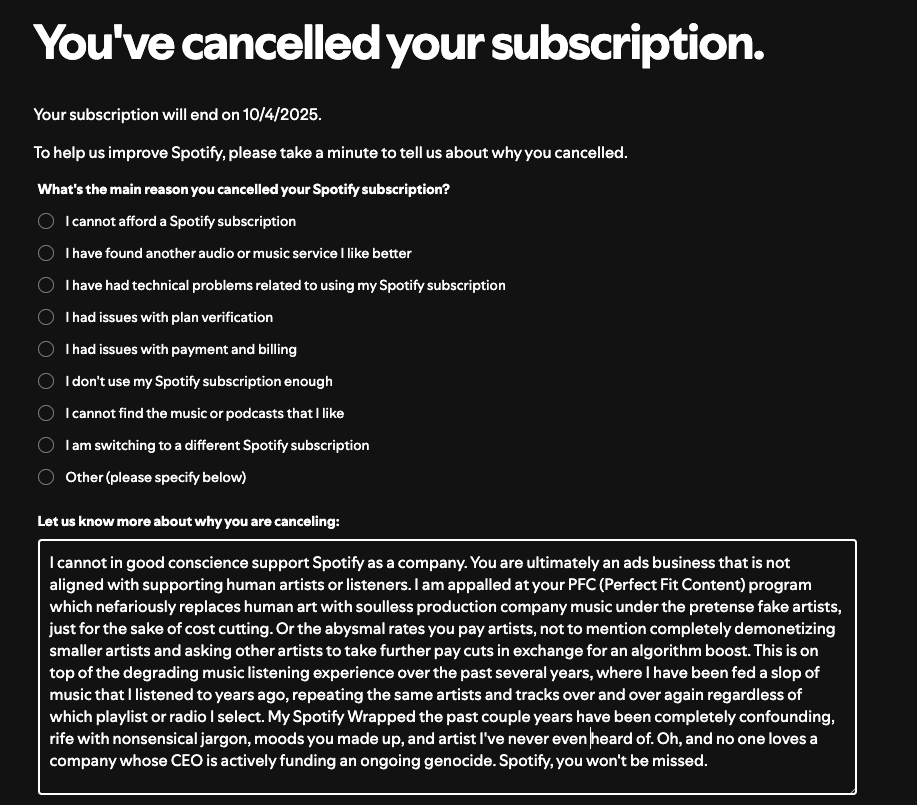

Knowing that I was writing this post, a friend sent me their reasons to cancel Spotify to use as a visual aid:

Spotify, a blessing and a curse. Spotify, something that has started to accompany every part of life, something you might struggle to stop using because you use it when you’re cooking, commuting, working out, to boost your mood, shut off your brain, find and share music with your loved ones, even as a “healthier” alternative to other coping mechanisms. Spotify, the one platform that has become synonymous with a musician or band “getting serious” and “going pro”, which they might have to use to reach and stay relevant to their fans, but can’t count on to sustain them financially. Over the weeks the issue only became more complex.

As Bobby Martinez (Dandy Boy Records) and Ebben Saunders (Psychic Radio) expressed, the value platforms like these bring to humanity aren’t easy to quantify. The world’s music at your fingertips, what a beautiful concept, Ebben said. How intimidating to have this access be controlled and limited by a concentrated corporate landscape in which economic incentives don’t necessarily align with social ones. We heard from Haneen Sidahmed (Sudan Tapes Archive), tresX X Arriaga Cuellar, and DJ JUANNY Jorge Courtade (Rebane Récords): it’s really a question of access. There are many worlds of music not online; finding them is an effort in and of itself. Many cannot afford to keep physical music collections, let alone double check that everything they consume is properly and fairly attributed. Some artists make music to survive. Others put the money to questionable use. Where do we draw boundaries as consumers and creators?

I began to realize in these conversations that having the agency to decide what forms of media and which artists we support is itself a luxury, a continuous learning process of our own values and belief, a true labor of love fraught with immense political and economic meaning.

Curation as a medium of connection and community

Our second week focused on radio. Gabriel Lopez (KEXP) spoke about an early memory of hearing a classic song on the radio in the car his parents had just bought, driving back home. Mohit Kohli (Fault Radio) talked about an adolescent ritual of discovering and putting on music, reading the liner notes, feeling a connection with the lyrics and artist, and later, finding confidence as a DJ, independence in working for himself. There was a process to discovering and identifying with music which took time, trial and error, and made finding your favorites more gratifying and memorable.

I was struck by something Neroli Devany (Humboldt Hot Air) said (paraphrased, pieced together from my barely legible notes):

“Society likes comfort. We always have to be occupied. We want to be able to skip the track if we don’t like it. Sometimes I’m driving and I find myself moving to skip before I realize it’s the radio… But by accepting we’re not in control, that this is important to someone, and there is a human behind that… The act of going and staying out of our comfort zones is what it takes to be part of something bigger. That’s what it means to be a part of a community.”

Neroli mentioned hearing radio DJs making mistakes live on air, playing tracks over each other, and appreciating that only a human could be behind such things. I feel a similar appreciation for musicians like Mac DeMarco, who spent years chain-smoking cigarettes and making low-budget music from a lofted bedroom studio in Bushwick (a fan commented in 2016, “he wouldn’t be Mac without his cigs”) before quitting smoking and drinking and releasing a nine-hour, 199-track, five-year, largely-instrumental album in 2023 I call his “sobriety album”:

“I look at the world and the music industry and maybe I just want to be more of an artist, or pretend to be. Because I mean, there are plenty out there, but I think there’s another side of the music industry where it is like sport. But I like seeing all the crap. The human part is the most important part to me in any kind of art. I guess I’m just trying to remain human.” — Mac DeMarco for NME

Tshego Letsoalo (KALW) told us about the time she stood still in her kitchen, not expecting to resonate so strongly with something that had suddenly come on the radio. It was bittersweet to register a fleeting moment of delight even as it passed. That, we agreed, was central to being human.

Music as a cultural discovery and preservation tool

We heard from sound archivists. Haneen talked about starting Sudan Tapes Archive during the pandemic — “I wanted to listen to childhood tapes. I’m very nostalgic” — a quest to preserve the original music she remembered being given by family in Sudan, but could not find anywhere. But, as many raised in multiple cultures can understand, asking questions and attempting to document familial and cultural history can be met with confusion, resistance, anger, and pain. Jorge told us about the challenge of seeking connection to Honduran roots when family members did not like to talk about the past, finding understanding and community in music that would “never have been recommended to me on Spotify, and if it wasn’t recommended to me, there’s no way it would have ever been recommended to you.”

At the same time, preservers of local and regional music have mixed emotions about widespread discovery, fearing conglomerates coming in to modify and market it to sell to a global audience without proper credit or payout to the original artists, popularizing a narrow perception of the complex culture and history behind the music. At best, this globalization can result in new sound, representation, and the fusion of communities; at worst, the virality is a fleeting, insulting bastardization of sound created by centuries of unity and strength in the face of hardship.

The soundtrack of my childhood was Whitney Houston, Michael Jackson, AC/DC, and The Eagles on my dad’s radio and unstructured, rambling piano lessons from my family’s next-door neighbor. She was a retired concert pianist who took it upon herself to design a custom music theory and piano performance training program for me, including observing my mistakes and writing out corrective exercises for me on blank sheet music. I have a distinct memory of watching her hands shake as she drew out a series of sixteenth notes for me to practice consistent technique until I perfected them, telling me to do my hand-stretching exercises every day to avoid developing the arthritis so many pianists suffer from later in life. My first out-of-body experience happened accidentally during a recital when I slipped out of consciousness and let my practice take over, felt my heart and time slow (see: this scene in Soul) as if I had become a medium between the composer and the audience, a vessel via which they could communicate across hundreds of years.

I’ve spent much of my life chasing this feeling, seeking to understand it, reproduce it, enhance it; finding new and unexpected iterations of it is one of my life’s most indescribable joys. Some might call it being “in the zone”, “locked in”, “flow state”; to me it’s more than that. It’s a sense of peace, order, and purpose that comes from finding and following missions I’m deeply, spiritually moved to keep pursuing.

Taste is learned but not taught

Called to action by this discussion and lecture series, I reflected on my own consumption habits. I’d spent more than ten years listening to music and watching television every chance I got; at work, at the gym, at home, on planes. My problem wasn’t with the media itself. It was that the same stream of mediocre media I was putting on to have something to distract me started becoming less effective over time. Because I wanted to delay the feeling of being bored as much as I could, and the same methods weren’t working as well, I started looking for ways to enhance my experience. I didn’t like being bored. Actually, I was scared of being bored. I felt it was important to be always on, always productive, and if I wasn’t doing something, I didn’t know what to do with myself.

I started playing albums from start to finish, no skips, minimal interruptions. I started paying to see movies in theaters, establishing an hours-long process of getting to the theater, watching the film critically, sitting through boring and uncomfortable scenes (and often being rewarded by something beautiful after), studying the details. I developed a taste for classic horror and foreign black-and-white film I truly never thought I’d have the stomach or intellectualism to appreciate. I discovered 3ee, re-discovered Teyana Taylor, and found parts of myself in films I would never even have watched without taking a leap of faith on the Roxie’s staff picks.

Taste, to me, is a constant learning process. Some things are immediate hits but diminish in gratification as you return to them; others unfold and multiply in complexity as you approach them in different contexts. Taste is subjective in the sense that you are the one most consistently present variable, also the hardest to quantify and replicate. This hard-to-model individuality is precisely what separates human from machine. Perhaps the one true humanistic thing we can do in a world of complex interactions and incentives is to continue revising and refining our individual tastes, to double down on independent, critical thought.

When I was a fairly small child, I began to eat the whole apple. Not just the flesh, but the core with all the pips in it, even the stem. Not because it tasted good, I don’t think, nor because of any idea I might have had that I shouldn’t be wasteful, but because eating the core and the stem presented an obstacle to pleasure. It was work of a kind, even if in reverse order: first the reward, then the effort. It is still unthinkable for me to throw away an apple core, and when I see my children doing it — sometimes they even throw away half-eaten apples — I am filled with indignation, but I don’t say anything, because I want them to relish life and to have a sense of its abundance. I want them to feel that living is easy. And this is why I’ve changed my attitude towards apples, not through an act of will, but as a result of having seen and understood more, I think, and now I know that it is never really about the world in itself, merely about our way of relating to it. Against secrecy stands openness, against work stands freedom.

— Karl Ove Knausgård, “Apples”, Autumn

This essay is absolutley stunning - you've articulated something I've felt but couldn't name about the tension between algorithmic convenience and human curation. The Neroli Devany quote about accepting we're not in control and recognizing "there is a human behind that" is so powerful. It reminds me that discomfort isn't a bug in the system - it's how we grow our taste. Your point about taste being learned but not taught really resonates. The apple core metaphor from Knausgård perfectly captures this - we can train ourselves to find value in difficulty, or we can optimize everything for effortless consumption. What Spotify's Perfect Fit Content represents is the latter taken to its logical extreme: music engineered to be consumed without effort, without growth. The archivists' stories about Sudan and Honduras highlight another crucial dimension - algorithmic discovery can't replicate the cultural context and familial histories that make music meaningful. When Jorge says certain music would never be recommended on Spotify, he's pointing to a fundamental limitation of collaborative filtering. Thank you for wrestling with these complexities so thoughtfully.